The magnificent black walnut trees in the heart of North America’s forests are under threat from a subtle but powerful foe. With the accuracy of a well-coordinated army, this threat—known as Thousand Cankers Disease (TCD)—causes serious ecological and financial harm.

Geosmithia morbida and the Walnut Twig Beetle are the culprits

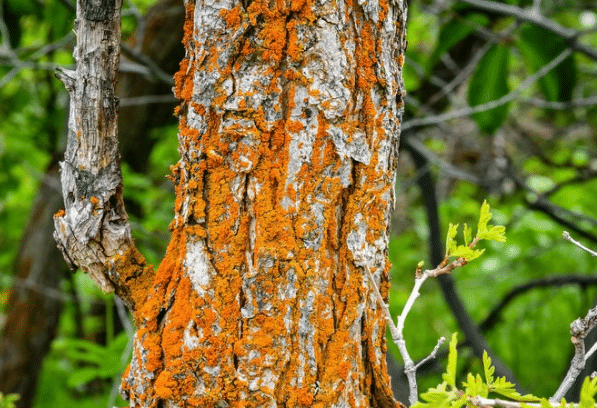

The fungus Geosmithia morbida and the walnut twig beetle (Pityophthorus juglandis) form a deadly alliance that leads to TCD. The tiny but incredibly numerous beetles drilled holes in the tree’s bark, providing the fungus with entry points. Many cankers, or dead patches on the bark, are created as a result of this invasion, impairing the tree’s capacity to carry nutrients and water, which finally causes it to die. Little deeds add up to a good world.

Thousand Cankers Disease Facts and Spread

| Category | Details |

|---|---|

| Disease Name | Thousand Cankers Disease (TCD) |

| First Identified | 2003 (Western USA), 2010 (Eastern USA), 2013 (Europe) |

| Primary Vector | Walnut Twig Beetle (Pityophthorus juglandis) |

| Causal Fungus | Geosmithia morbida |

| Affected Trees | Black Walnut, English Walnut, Paradox rootstocks |

| Symptoms | Dark cankers, bleeding bark, crown dieback, tiny beetle holes |

| Regions Impacted | Western U.S., Tennessee, Italy (Veneto), and expanding |

| Prevention | Sanitation, early removal of infested trees, no chemical control |

| Reference Source | USDA Forest Service |

Dispersion and Effect

Since its discovery in the western United States, TCD has steadily spread eastward, making its way to states like Ohio, Indiana, and Tennessee. Known for its nutritious nuts and superior wood, the black walnut (Juglans nigra) is especially vulnerable. There are significant economic ramifications; for example, Missouri estimates that if TCD infiltrates the state, it could lose $850 million in wood and nut production over the course of 20 years.

The diagnosis and symptoms

It is difficult to identify TCD in its early stages. Yellowing and wilting of the leaves, mostly in the upper canopy, are the first signs. Branches die off as the disease worsens, and the tree shows many tiny cankers under the bark. These cankers frequently group together, girdling branches and obstructing the flow of nutrients. Another warning indicator is the existence of tiny, pinprick-like beetle entry holes.

Current Techniques for Management

As of right now, TCD has no known cure. Management prioritizes cultural norms and preventative measures:

- Maintenance of Tree Health: Making sure trees receive adequate fertilizer and irrigation can strengthen their resistance to pests and illnesses.

- Sanitation: Beetle populations can be decreased by removing and appropriately disposing of infected trees and debris. Because infested wood can harbor beetles and aid in the spread of the disease, it is best to destroy it.

- Movement Restrictions: To stop the disease from spreading, quarantines must be put in place and the transportation of walnut wood from afflicted areas must be discouraged.

Investigations and Prospects

The scientific community is working hard to find ways to fight TCD. Among the research initiatives are:

Types That Are Resistant:

investigating genetic resistance in walnut species in order to create cultivars that are resistant to TCD.

Biological Regulation:

looking into diseases or natural predators that prey on the walnut twig beetle.

Chemical Procedures:

The behavior of the beetle and the value of the tree limit the effectiveness of current chemical controls, but research is still being done to find efficient insecticides and fungicides. WInsconsin Gardening